Places of Refuge, Elderly Terrains

…Having considered North Korea’s leisure history in order to contextualise both the notion of non-productive or leisurely space under Pyongyang’s remit and to consider some of the political and ideological imperatives which underpin the production and development of such spaces the paper’s narrative arrived at what is essentially a space for families and children. While this paper does in fact address some elements of childhood experience in North Korea and will examine them in the light of these leisurely spaces by the Taedong, it is not the spaces of family that are of interest to this author, but to what might be regarded as the potentially more hidden spaces of the disabled and the orphaned.

North Korea has not been known for its kind treatment of those who do not fit within its social and ethical model. Hazel Smith in her recent book ‘North Korea: Markets and Military Rule” for instance expressed astonishment at North Korean census figures from 2010 which at least suggested that teenage or non-normative pregnancy might be a fact in North Korea (recording some 156 births to mothers under the age of 16 in 2010), having never done so before (Smith, 2015, p.231). London’s Paralympic Games in 2012 was the first recorded instance of a disabled athlete competing in public for North Korea and research by this author (Winstanley-Chesters, 2015a), has sought to unpick the connections between this fact and work focused on institutional capacity building between the North Korean Ministry of Health and the United Kingdom’s Foreign and Commonwealth Office. Other nations (both autocratic and democratic) in history have sought to eradicate those who are differently or dis-abled, Nazi Germany of course seeking to exterminate the unfit and the unwell, and Sweden having a long standing policy of forced sterilisation of those with Learning Difficulties and Difference, only ending in the early 1980s being simply two disparate examples. Whether North Korea ever sought by policy means to do so is unknown, but there has been much speculation as to the fate of those who by their physical or mental natures could not hope to be as productive as the general citizenry under Pyongyang’s sovereignty.

Of course there is nearly always one category of disabled or differently abled citizens who are not regarded as burdensome by nations or territories, quite the opposite in fact their support and rehabilitation is often seen as a focus of national commitment and social duty, soldiers and people of uniform. There is a huge body of research focused on the functionality and suitability of veterans and service people’s support post combat in a number of sovereignties and nations, but absolutely none it seems addressing North Korean veterans and service people and the provision of services to them. While this paper cannot hope to cover their experience holistically or comprehensively it can at least, with a Geographer’s eye begin to present some of the political and physical terrain of these services and their experience.

“You disabled soldiers fought heroically against the US imperialist aggressors and shed your blood to defend the motherland during the last war. It is really admirable that, although seriously disabled, you are taking an active part in the building of socialism” (Kim Il-sung, 1958, p.214).

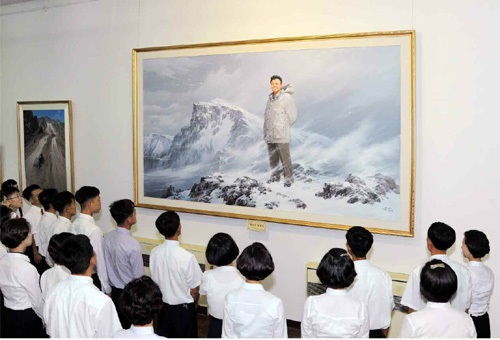

Kim Il-sung’s statement, recorded in the Works series for 1958 as “We must take good care of disabled soldiers who shed their blood in the fight for the country and the people”, and apparently given at a workshop for disabled soldiers is the foundation statement so far as North Korean ideological conceptions of disabled ex-employees and service people is concerned. While a tremendous debt is acknowledged to those who have become disabled through military combat for their nation (“We must scrupulously look after the disabled soldiers in every respect so that they will not suffer any inconveniences both in life and in work” (Kim Il-sung, 1958, p.214), the individuals themselves are not absolved from commitments to the national cause, nor the strictures of revolutionary fervour. Disabled soldiers should, even in this space and place of refuge, work and be as productive as possible: “…you should do some work. Yet, you should never overwork yourselves. It will be good to work as much as necessary to keep yourselves fit.” (Kim Il-sung, 1958, p.216). Given this apparent focus on productivity and as an example to be followed, those who were resident in this particular workshop were to be amply supplied to enable their work; “The disabled soldiers here want more fruit gardens. So it will be a good thing to give them the state orchard in the vicinity of the workshop…The disabled soldiers should be supplied with both fuel for production and firewood for home use” (Kim Il-sung, 1958, p.2014). As with other citizens of North Korea, the disabled should be supported further in their education and personal development, and prejudice which might be problematic to that end be resisted: “Now a comrade claimed that once he went to a school for disabled soldiers, only to be rejected and returned back because he had arms missing. The cadres at the school did the wrong thing. Could it be that one who has no arms cannot study?” (Kim Il-sung, 1958, p.216). Disabled ex-service people within the text are widely anticipated to engage in education at all levels and within all institutional structures provided.

However, along with work itself, disabled soldiers and service people who have essentially fought for the North Korean revolution (within this text, the fighting which disabled them would have been during the 1950-1953 war against United Nations and Republic of Korea forces), should not neglect or forget that revolution. The Disabled must be as good and as ideologically sound North Koreans as any other, as committed and as respectful of its revolutionary traditions as they were during their combat: “Disabled soldiers should always love the people and hate only the enemy. As you fought well and courageously for the motherland and the people on the battlefields in the past, you should today continue to have the same revolutionary spirit…” (Kim Il-sung, 1958, p.217). With this revolutionary spirit and commitment comes an ethical framework familiar surely to all North Korean political and Party appointees: “Our disabled soldiers should lead a simple life and always live in a revolutionary way. Under no circumstances should they drink alcohol and say things under its influence…” (Kim Il-sung, 1958, p.217).

Such spaces of refuge and support for the once militarily committed are of course therefore not to be spaces of refuge from the politics of North Korea and the demands of revolutionary ideology. In a sense past examples such as Kiluiju Disabled Soldiers Production Workshop are a reflection and a projection of this into the contemporary era and into the impetus and imperatives which underpin North Korean healthcare more generally. ‘On Making Good Preparations for Universal, Free Medical Care’ for instance a 1952 instruction from Kim Il-sung, and one of a number focused on the post Korean War rehabilitation of a devastated if optimistic North Korean bureaucracy and the form of state and infrastructure anticipated in the post War era, contains a pre-figuring of the sort of support and impetus behind such projects for the disabled. “Nothing is more precious to us than the lives of the people. At present our people are struggling both at the font and in the rear dedicating all they have to final victory in the war. What is it that we cannot spare people who fight selflessly, displaying noble patriotism and mass heroism” (Kim Il-sung, 1952, p.19).

While the terrain of Kiluiju Disabled Solders Production Unit of course is now in the distant historical past of North Korea and either photos nor contemporary reportage other than that recorded in Kim Il-sung’s Works and Selected Works are very difficult to access, North Korea’s ideological course as only consolidated institutional focus around the needs of military infrastructure and personnel in recent years. Kim Jong-il’s development of a Songun or Military First politics following the death of his father in 1994 entailed the wholescale revision of Party and governmental policy as well as institutional capacity. Food distribution, rationing and health infrastructure were heavily focused on supplying and supporting North Korea’s military. The infrastructure focused on the refuge of the elderly and the disabled has similarly developed, though with definite connections to the past calls for those resident to live productive and revolutionary lives, well emplaced within the wider superstructures of North Korean politics and ideology. Pyongyang’s newly built ‘Home for the Aged’ is just such a piece of infrastructure.

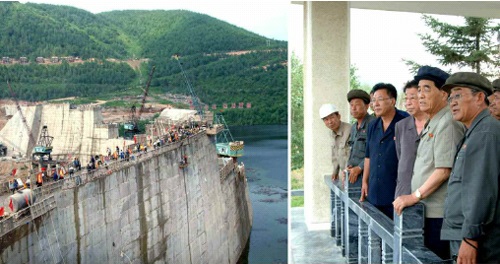

Amongst the pleasure and leisure spaces introduced earlier in the paper on the banks of the Taedong River, the Home for the Aged was completed and opened in early August 2015 (KCNA 2015a). While the images presented in the Rodong Sinmun (Rodong Sinmun 2015b) and KCNA (KCNA 2015a), undoubtedly present the home as part of Pyongyang and North Korea’s modern urban infrastructure and development and very much an element of governmental bequest in the age of Kim Jong-un, the reportage leading up to its opening makes very sure to connect to earlier eras and the revolutionary authority (Kwon and Chung, 2012), present within the historical narrative. Kim Jong-un for instance on visiting the still under construction building in March of 2015 is recounted as having; “…recalled with deep emotion that President Kim Il-sung, together with leader Kim Jong-il, visited an old service people’s home in Manal-ri, Sungho County in May 1948 when he was busy paving an untrodden path for nation-building and showed deep emotion for the inmates living conditions…saying that the state would take warm care of the aged…” (Rodong Sinmun 2015a). The home and its construction is also firmly fixed in the governmental and bureaucratic ecosystem of North Korea, reportage and documentation focused on the process paying both homage and careful articulation to/for the respective positions of both the Workers Party of Korea and the Korean People’s Army. Kim Jong-un remarked for instance during his March visit that “to build the home for the aged well is a very important work in correctly implementing the Worker’s Party of Korea’s policy for the care of the elderly and fully displaying its validity and vitality” (Rodong Sinmun, 2015a) and also, in a nod to the military’s role in its construction “expressed belief that the soldier-builders would successfully complete the construction of the home by late June, true to the intention of the Party Central Committee” (Rodong Sinmun, 2015a).

Even of course while focusing on bureaucratic and institutional niceties and the process of the Home for the Aged’s construction, North Korean reporting makes clear to assert the wider framework for the care of the disabled, elderly and combat injured service people as of 2015 in North Korea: “Under the paternal love of Kim Il-sung and Kim Jong-il, the ‘DPRK Law on the Protection for the Aged’ was adopted in the country and the Central Committee of the Federation for the Care of the Elderly of Korea organized and the Party and the state have wholly taken charge of aged and disabled people’s health and life…” (Rodong Sinmun, 2015a). The Home itself will it seems also serve to drive further and future developments in the care and service provision so far as spaces of refuge for the elderly and disabled are concerned: “The Pyongyang City Home for the Aged should be built as a prototype equipped with all conditions for its inmates to lead a happy life free from any cares and worries so that such homes can be constructed in localities with it as a model…” (Rodong Sinmun, 2015a)

As a space of refuge and care for the disabled, elderly and disabled service people, Pyongyang’s new Home for the Aged is in summary presented as a space of comfort and refuge meant it seems to be in tune with some of the more comforting and less rigorous elements perhaps seen in Nursing Homes and accommodation or refuge spaces for the elderly in the United Kingdom and elsewhere (particularly the Netherlands developing network of Alzheimer’s Villages, in which the environment residents are placed is designed to reflect their own social constructs and life experience (Henley, 2012)). Kim Jong-un notes for example on its opening that “the home was successfully build to suit national character and flavour…dining rooms were constructed to create homelike atmosphere” (Rodong Sinmun, 2015b). However the terrain of the Home of the Aged is also presented as one of acute and definite modernity, in tune with many of the governmental priorities and agendas of the day. Kim Jong-un himself remarks that “the longer one watches, the more fashionable it looks” (Rodong Sinmun, 2015b) and that in common with the infrastructure created in the 1950s to support not only the physical rehabilitation, but the political and social rehabilitation of disabled and injured service people, the home’s residents will not be allowed or afforded the opportunity to neglect their personal development. Kim Jong-un’s opening speech includes the assertion that “…service and healthcare establishments including barber’s, beauty parlor, bath and treatment rooms look impeccable and library, sporting room and amusement hall were also successfully built for the cultural and emotional life and physical training of health seekers” (Rodong Sinmun, 2015b). While their social and revolutionary health will be maintained, it will of course be done so in a structure that is environmentally friendly and ecologically sound in the manner that North Korea presents much of its infrastructural development in recent years; “an air conditioning system by use of geotherm is introduced into the home…and greening is it environment done very well” (Rodong Sinmun, 2015b).

While the Home for the Aged is a distinct piece of architecture by itself therefore it is meant to be encountered within the wider terrain of development and infrastructure of its time. This is even more assertively established by the fact of its position, “built on the bank of the River Taedong in the wake of the Pyongyang Baby Home and Orphanage” (Rodong Sinmun, 2015c). This terrain includes this connection with the afore named neighbouring facility, which allows the author and the paper to move to the opposite end of life’s spectrum, but in North Korea’s governmental mind-set adjoined in continuing efforts to demonstrate “vividly President Kim Il-sung and leader Kim Jong-il’s love for the people” (Rodong Sinmun, 2015b)…

______________________________________________________

Reference List

Armstrong, Charles. 2002. “The Origins of North Korean Cinema: Art and Propaganda in the Democratic People’s Republic.” Acta Koreana 5,1: 1-19.

Armstrong, Charles. 2011. “Trends in the Study of North Korea.” The Journal of Asian Studies 70, 2: 357-371.

Berthelier, Benoit. 2015. “Collective Identities and Cultural Practices in the North Korean Movement for the Popularization of Arts and Letters (1945-1955), Conference Paper delivered at the Association for Korean Studies in Europe annual conference, July 2015, Bochum, Germany.

Bonner, Nick and Daniel Gordon. 2004. A State of Mind (film). Kino International/BBC Films

Burgoyne, Susan. 1969. “The World Youth Festival”, Australian Left Review 1, 17: 45-49.

Cha, Victor. 2012. North Korea: The Impossible State. London: The Bodley Head.

De Ceuster, Koen. 2003. “Wholesome Education and Sound Leisure: The YMCA Sports Programme in Colonial Korea.” European Journal of East Asian Studies 2,1: 53-88.

Delury, John. 2013. “Park vs. Kim: Who Wins this Game of Thrones,” 38 North, June 18th, 2013, accessed January 20th, 2015, http://38north.org/2013/06/jdelury061813/

Dobrenko, Evgeny. 2007. The Political Economy of Socialist Realism. New Haven: Yale University Press.

Fahy, Sandra. 2015. Marching Through Suffering: Pain and Loss in North Korea. New York Cit, NY: Columbia University Press.

Henley, John. 2012. “The Village Where People have Dementia…and Fun”, The Guardian, 27th August, 2012, accessed 15th December, 2015, http://www.theguardian.com/society/2012/aug/27/dementia-village-residents-have-fun.

Joinau, Benjamin. 2014. “The Arrow and the Sun: A Topo-mythanalysis of Pyongyang.” Syunkyunkwan Journal of East Asian Studies 14, 1: 65-92

KCNA. 1997. “Korea’s City Management,” KCNA, September 5, 1997, accessed January 22, 2015, http://www.kcna.co.jp/item/1997/9709/news9/05.htm#12

KCNA. 1998. “Thongil Street,” KCNA, February 11, 1998, accessed January 22, 2015, http://www.kcna.co.jp/item/1998/9802/news02/11.htm#9

KCNA. 2003. “Rungna Islet,” KCNA, May 21, 2003, accessed January 22, 2015, http://www.kcna.co.jp/item/2003/200305/news05/22.htm#7

KCNA. 2007. “Pleasure Ground Newly Built in Mangyongdae,” KCNA, April 17, 2007, accessed January 22, 2015, http://www.kcna.co.jp/item/2007/200704/news04/18.htm#10

KCNA. 2012. “Rungna People’s Pleasure Ground Opens in the Presence of Marshall Kim Jong Un,” KCNA, July 25, 2012, accessed January 22, 2015, http://www.kcna.co.jp/item/2012/201207/news25/20120725-34ee.html

Kim Il-sung. 1947. “On Improving the Public Health Service.” Works. Vol 2. Pyongyang: Foreign Languages Publishing House.

Kim Il-sung. 1951. “On Some Questions of Our Literature and Art.” Selected Works Vol. 1. Pyongyang: Foreign Languages Publishing House.

Kim Il-sung. 1952. “On Making Good Preparations for Universal Free Medical Care.” Works. Vol 6. Pyongyang: Foreign Languages Publishing House.

Kim Il-sung. 1953. “Everything for the Postwar Rehabilitation and Development of the National Economy.” Works. Vol 7. Pyongyang: Foreign Languages Publishing House.

Kim Il-sung. 1958. “On the Immediate Tasks of City and Country People’s Committees.” Selected Works Vol. 2. Pyongyang: Foreign Languages Publishing House.

Kim Il-sung. 1958. “We Must Take Good Care of Disabled Soldiers Who Shed Their Blood In the Fight for the Country and the People.” Works. Vol 12. Pyongyang: Foreign Languages Publishing House.

Kim Il-sung. 1966. “Let us Produce More Films Which are Profound and Rich in Content.” Works. Vol 20. Pyongyang: Foreign Languages Publishing House.

Kim Il-sung. 1966. “The Communist Education and Upbringing of Children is an Honourable Revolutionary Duty of Nursery School and Kindergarten Teachers.” Works. Vol 20. Pyongyang: Foreign Languages Publishing House.

Kim Il-sung. 1972. “On Developing Physical Culture.” Works Vol 27 .Pyongyang: Foreign Languages Publishing House.

Koh, Byung Chul. 2005. “’Military-First Politics’ and ‘Building a Powerful and Prosperous Nation’ In North Korea.” Nautilus Institute. http://nautilus.org/napsnet/napsnet-policy-forum/military-first-politics-and-building-a-powerful-and-prosperous-nation-in-north-korea/. Accessed January 30 2015.

Kurbanov, Sergei. 2015. “North Korea One Year Before the 13th Festival of Youth and Students: Trends and Changes”, Conference Paper delivered at the Association for Korean Studies in Europe annual conference, July 2015, Bochum, Germany.

Kwon, Heonik and Byung-ho Chung. 2012. North Korea: Beyond Charismatic Politics. Lanham: Rowman and Littlefield.

Kwon, Heonik. 2013. “North Koreas New Legacy Politics.” E-International Relations, May 16th, 2013, http://www.e-ir.info/2013/05/16/north-koreas-new-legacy-politics/.

Myers, Brian. 2012. The Cleanest Race: How North Koreans See Themselves and Why It Matters. New York: Melville House.

Myers, Brian. 2015. North Korea’s Juche Myth. Seoul. Sthele Press.

Rodong Sinmun. 2014. “Hamhung Water Park Built Newly,” Rodong Sinmun, January 4, 2014, accessed January 22, 2015, http://www.rodong.rep.kp/en/index.php?strPageID=SF01_02_01&newsID=2014-01-04-0034&chAction=S.

Rodong Sinmun. 2015a. “Kim Jong-un Inspects Pyongyang City Home for Aged under Construction”, Rodong Sinmun, March 6th, 2015, accessed 15th December, 2015, http://www.rodong.rep.kp/en/index/php?strPageID=SF01_02_01&newsID=2015-03-06-0008

Rodong Sinmun. 2015b. “Kim Jong-un Provides Field Guidance to Newly Built Pyongyang Home for Aged”, Rodong Sinmun, August 3rd, 2015, accessed 15th December, 2015, http://www.rodong.rep.kp/en/index/php?strPageID=SF_02_01&newsID-2015-08-03-0016.

Rodong Sinmun. 2015c. “Kim Jong-un Visits Pyongyang Baby Home and Orphanage on New Year’s Day”, Rodong Sinmun, January 2nd, 2015, accessed 15th December, 2015, http://www.rodong.rep.kp/en/index.php?strPageID=SF01_02_01&newsID=2015-01-02-0021

Rodong Sinmun. 2015d. “Kim Jong-un Provides Field Guidance to Wonsan Baby Home and Orphanage Close to Completion”, Rodong Sinmun, April 22nd, 2015, accessed 15th December, 2015, http://www.rodong.rep.kp/en/index.php?strPageID=SF01_02_01&newsID=2015-04-22-0016.

Rodong Sinmun. 2015e. “Kim Jong-un Provides Field Guidance to Wonsan Baby Home and Orphanage”, Rodong Sinmun, June 2nd, 2015, accessed 15th December, 2015, http://www.rodong.rep.kp/en/index.php?strPageID=SF01_02_01&newsID=2015-06-02-0018.

Smith, Hazel. 2015. North Korea: Markets and Military Rule. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Vorontsov, Alexander. 2006. “North Korea’s Military First Policy: A Curse or a Blessing.” North Korea Review. 2, 2: 100-102

Winstanley-Chesters, Robert. 2014. Environment, Politics and Ideology in North Korea: Landscape as Political Project. Lanham: Lexington Books.

Winstanley-Chesters, Robert. 2015a. “The Socialist Modern at Rest and Play: Spaces of Leisure in North Korea.” Academic Quarter, 11 (Summer 2015): 196-211.

Winstanley-Chesters, Robert. 2015b. “’Patriotism Begins with a Love of Courtyard’: Rescaling Charismatic Landscapes in North Korea.” Tiempo Devorado (Consumed Time), 2 (2015): 4-26.