Developmental connectivity in the Tumen Triangle: Potato, “King of Crops”

“We want to live our own lives in our own way.”2

Although located a continent away, development in the peripheral spaces of the United Kingdom is not entirely unlike that of the northern half of the Korean Peninsula, and nor are the challenges presented by individual and institutional agendas entirely novel. In the UK, peripheries and borderlands are abound; Lord Leverhulme’s paternalistic and impositional conception of economic and environmental possibility in Stornoway and the Isle of Lewis at the turn of the twentieth century is fairly typical of grand schemes and projects in the marginal spaces of the British Isles. Development in the periphery of any nation can thus appear peripatetic, marked by hard-to navigate realities and unsatisfactory outcomes. Undeniably, the areas investigated by the Tumen Triangle Documentation Project were once regarded as peripheral, distant, and marginal spaces, though this has become much less true in recent times. Ryanggang Province is arguably the most peripheral and distant of the provinces of the Tumen borderland. Comprising much of the DPRK’s interior northern border with China, Ryanggang is mountainous and forested, regarded by Kim Il-sung as a safe space even in the throes of war. Representing as it does the border with China’s Changbai region, the province is about as far from Pyongyang and the institutional centers and structures of charismatic Kim-ism as one is likely to find. This essay serves as a demonstration of the assertion that no matter how peripheral a space may be, developmental approaches can be enacted within it by both local institutions and national agendas.

Within national industrial strategy, Ryanggang has long been regarded as dysfunctional, but is also home to a now operative copper mine,3 the only such mine in North Korea. It is also key to the historical narrative of Kimist legitimacy due to the presence of the Mt. Baekdu4 massif with its accompanying Korean genesis mythos and authority- and legitimacy-generating narratives of Kim Il-sung’s guerrilla struggle and the birth of Kim Jong-il. Given the presence of Mt. Baekdu and wider knowledge of the topography of the Korean peninsula, it will not have surprised the reader to learn that the province is both highly mountainous and quite heavily forested. What might be surprising would be to learn if such a peripheral, marginal space played an important role within national political narratives. While it is not possible to declare that the province and its provisional locus of power, Hyesan, have always been at the center of agricultural possibility in North Korea, narrative connections do start comparatively early. However, general systemization of these connections did not occur cohesively until the publication of Kim Il-sung’s “Theses on the Socialist Rural Question in our Country”5 in 1964.

However, what are termed “foundational events” in North Korea’s developmental and agricultural sectors can be found prior to 1964. Examples include the Potong River Improvement Project in 1946 (foundation for the hydrological sector), or the tree planting on Munsu hill (also in 1946 and used as a foundational moment in the forestry sector).6 This is also true of Ryanggang Province.

1958 saw the publication of the text “Tasks of the Party Organizations in Ryanggang Province,” ostensibly a recounting of an “inspection” tour made by Kim Il-sung in May of that year. Unlike a number of similar tours or moments of guidance in North Korean narratives, activities in the province appear to have deeply impressed the Great Leader, who stated that “considerable progress has been made so far in Ryanggang Province, which formerly was a backward region,” and going on to cite “great achievements [which] have been made in all fields of politics, economy and culture.”7

Ryanggang is marked out as needing to adopt a particularly local yield and production strategy, distinct from elsewhere in the North Korea of the time. Whereas the 1950s saw a great deal of focus on increasing the production of rice and grain in North Korean agriculture, Ryanggang was to adopt measures seen much more recently in the North’s media output, and which can be thematically connected to this earlier era, establishing a line of narrative connectivity stretching back comfortably far.

In short, Ryanggang was to focus on the realm of the tuber. In his marked observational style, Kim noted: “Potato is a high-yielding crop in Ryanggang Province. In this province potato, not maize is the king crop of dry fields.”8 It seems as if farmers, cooperatives and collectives had previously utilized this non-normative agricultural output goal (non-normative in the context of East Asia), but not to the extent required by Kim: “In plays and sketches you presented for us, you boasted so much about your potatoes. Although you are very proud of your potatoes, the area allotted to potato crops is small.”9 Accordingly, agriculturalists and their institutions in Ryanggang are to disregard the non-normative element of this approach. (“Some people seem to be become baffled and worried when they hear me saying this [and make production of tuber the key goals].” 10 Kim Il-sung went so far as to call for all land (with the exception of “the areas marked for industrial crops”) to be planted with potatoes.11

North Korean state narratives are marked by repetitive practice and connectivity between sectors. Thus, just as in the forestry sector, the agricultural sector of Ryanggang must “learn by doing” (or by not doing as the case may be). Kim Il-sung’s next interaction would be on much more combative terms, as, similar to foundational events or themes, secondary visits of chastisement are familiar in North Korean narratives.

Four years later, a return visit is documented in the forceful “Tasks of the Party Organizations in Ryanggang Province” from August 1963 (the same title), the introduction to which asserts that “you should not become complacent with successes already registered…you should maintain the spirit of advance and continue to battle hard.”12 While it seems that for the most part Kim was satisfied with developments, in the agricultural field it was a different matter: the section addressing the sector begins with the statement “the output of Ryanggang Province in negligible compared with that of other provinces.”13 Potato development has not apparently been at the forefront of institutional priorities within the province, or at least not in the way envisaged by Kim. In fact Kim refers to his previous visit for contrast “potatoes must not be planted without considering the consequences. I once said that the potato was king of the dry-field crops.”14 Agricultural workers have entirely misunderstood Kim’s direction and emphasis so that “Ryanggang Province grows it [potatoes] even in rice paddies and maize fields. This should not be done,” and requires reiteration of the policy with extra explanation: “You should not plant potatoes in areas where rice and maize grow well. The potato is king of dry-field crops in the highlands where grain does not grow well.”15

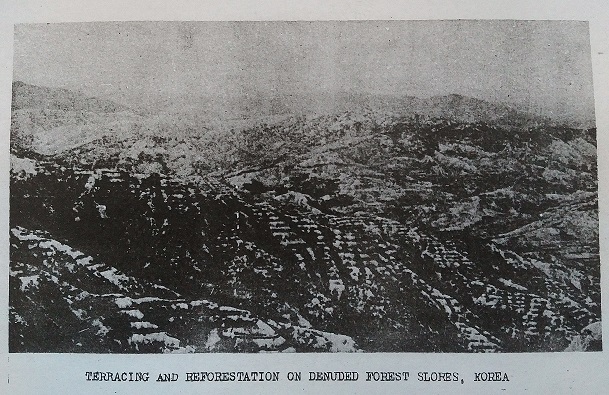

1964’s “Rural Theses on the Socialist Rural Question” principally focused on the systematization of productive and resource-driven agricultural approaches, and although it included calls for the adoption of a wider repertoire of productive strategies it did not address peripheral spaces or non-normative markets or production. Following the publication in May of 1964 of “Let Us Make Better Use of Mountains and Rivers,” Kim Il-sung embedded the “Rural Theses” approach within the forestry sector and the wilder geographies of North Korea, and in December the text “For the Development of Agriculture in Ryanggang Province” appeared.

Within that, institutional focus shifted from direct focus on potato focused agriculture, apparently at the behest of “scientificization” and “technicalization,” key themes of the Theses. In light of the provincial authorities continued failure to follow Kim Il-sung’s direction (“this province has not carried out the Party’s policy thoroughly and has failed to improve farming methods. Because farmers have continued to grow only potatoes on land where they can cultivate other grain crops, they gave been unable to produce sufficient grain. Even the potato crop has been attacked by disease and its seeds have degenerated.”16) the institutions of Ryanggang are further instructed to take light of developments in agricultural research which have begun to focus expertise on agricultural practice at altitude. Intriguingly under this new industrial-scientific approach, it is grains and legume crops that are relegated to a different category of marginal land; “as a matter of course, in those areas which have a lower altitude than 1000 meters above sea level you should continue to grow…potatoes widely.”17 #

As perhaps is now common knowledge, institutional and charismatic narratives have a tendency to contradict each other, and hence Ryanggang’s potato agriculture appearance in 1974’s “Let us Make Ryanggang Province a Beautiful Paradise” firstly features a slightly bizarre anecdote from Kim Il-sung’s guerrilla campaigning, in which the Great Leader has a disappointing, difficult encounter with the potato: “During the anti-Japanese armed struggle I lived on nothing but potatoes at the secret camp of the Tenth Regiment. I stayed with the regiment for nearly one month…they were reasonably good for a few days, but later it was hard to eat them.”18 However even in the mid 1970’s potatoes are in still in institutional focus in the context of the province; as Kim wrote, “it would be desirable to plant them in wide areas because their yield is high…your province should make [potato] syrup and supply it to the children and working people in the province, including the workers in the forestry and mining sectors, and to the visitors to the old revolutionary battlefields.”19

The level of relevance of potato production within institutional and narrative priorities and accompanying tuber-related science is difficult to ascertain in the decline of the 1980s and the chaos of the 1990s. However, if there is one thing in North Korean charismatic politics that is more predictable than the tendency towards repetition, it is the utilizable nature of themes from previous Kimist eras in contemporary times. It would not thus be surprising if Ryanggang echoed the institutional memory and memorialization of the province under Kim Il-sung in the era of Kim Jong-un the Young Generalissimo.

The first stage in the recovery of a dormant theme is its reiteration under a previous incarnation of Kimist legitimacy and authority. Kim Jong-il, according to this author’s reading, had very little to say on the matter of potato production, the narratives addressing tuber husbandry under the Dear Leader’s reign being extremely hard to follow. However, recently narrative connections began to be made in this area.

It is recounted, for example, that Kim Jong-il made a visit in October 1998 to Taehongdan County in Ryanggang during which he “initiated a proposal on bringing about a radical turn in potato farming” and “set the county as a model in potato farming and put forward tasks and ways for a leap in potato farming.”20 This visit and this desire to see potato production focused on the peripheral spaces of the Tumen Triangle once more. The necessary text setting all of this out is referred to as “On Bringing about a Revolution in Potato Farming.” Aside from the determination to initiate and drive development in a conventional yield-based direction, potatoes and Ryanggang are connected here with North Korea’s almost cultic or fetishistic approach to science and research. Further reportage notes this: “there is in Taehongdan County a well-furnished Potato Research Institute under the Academy of Agricultural Science, which solves the issue of potato seeds in our own way.”21

Of course the next important element of this rediscovery and repositioning is that the themes be brought into the present day, preferably in the same geographical locale and physical space. Hence in May of 2012 Rodong Sinmun reported that “Potato planting began in Taehongdan Plain, Ryanggang Province,” making sure of course to note that “the officials of the ministries and national institutions also went down to the fields to help the farmers in carrying out the behests of leader Kim Jong Il.”22

Unlike the almost random inculcation of interest in potatoes that marked the drive and development of the sector initially under Kim Il-sung (in 1958), this is an element that not only echoes the assertions and apparent considerations of both previous Kims, but also the framework instituted under the 1964 Rural Theses which instigated concern for scientific development. Taehongdan and Ryanggang’s exploits in the field of potato development would be harnessed by the need for all of it to at least appear possessed of a deep commitment to empiricism and evidence-based practice. Wonsan University of Agriculture’s “Bio-Engineering Institute,” for instance, is noted in the narrative as having “succeeded in breeding a new species of potato, which contains much starch and makes it possible to raise the per-hectare yield by far, pooling their wisdom and efforts.”23 There are other similar appearances by Pyongyang’s “Agro-Biological Institute,” which has been “culturing virus-free potato tissues in a scientific and technological way.”24

North Korea’s “Byungjin line” approach can seem a long way away from the potato fields of Ryanggang; however, the line’s parallel conception of political, ideological and institutional formation, utilizing as it does twin themes of nuclear deterrent strength and scientific/technological development, allows such apparently peripheral elements as potato production in the Tumen Triangle to both contribute to and be directed by the line.25 The focus on scientific and technological ways of approach potato and tuber research, based in the paradigms of pure science but harnessed by goals of capacity increase and efficiency, is also driven by a long asserted desire to embed multi-functionality in productive sectors. Hence, perhaps, the potatoes emerging from the marginal earth of Ryanggang will not simply be consumed in the conventional manner, but through the efforts of “Byungjin science” adopt radically different forms. “The Foodstuff Institute of the Light Industrial Branch” for instance was recently recorded as having “added much to the variety of processed potatoes by producing sweet drink, lactic fermented sweet juice, lactic fermented carbonated juice with potato.”26

Ultimately what Byungjinization allows for and promotes by way of its multi-stranded development approach has always been possible and desired in the North Korean institutional mind. As we can see from the case of Ryanggang up in the Tumen Triangle and developments surrounding the production, research, and development of tuber-focused agriculture, marginal and peripheral spaces can always be utilized and harnessed for the requirements of narrative development. The narrative of the anti-Japanese guerrilla struggle undertaken by Kim Il-sung, from which Kimism draws much of its authority and which serves as the genesis myth and mythos for the North Korean political, reflects this most of all, but marginal narratives such as potato production at Taehongdan equally reflect this tendency. Ryanggang’s potatoes and other counties and provinces of the Tumen Triangle may indeed be a long way from the institutional and narrative heart of the nation in Pyongyang, but, in terms of narrative, the Tumen Triangle and its developmental spaces are right next door.

1 Readers may find that some of the links to official North Korean documents are dead. This is a direct result of amendments to online archives made on the North Korean side following the purge of Jang Song-taek in December 2013. 2 John R. Gold and Margaret M. Gold, “To Be Free and Independent: Crofting, Popular Protest and Lord Leverhulme’s Hebridean Development Projects, 1917–25,” Rural History (1996), 191-206. 3 “China-N.Korea JV starts production at copper mine,” Reuters, September 20, 2011. 4 Benoit Berthelier, “Symbolic Truth: Epic, Legends, and the Making of the Baekdusan Generals,” Sino-NK, May 17, 2013. 5 Robert Winstanley-Chesters, “Treasured Swords Redux: (Re)Construction and the ‘Rural Theses’ of 1964,” Sino-NK, June 21, 2013. 6 Robert Winstanley-Chesters, “Forests as Spaces of Revolution and Resistance: Thoughts on Arboreal Comradeship on a Divided Peninsula,” Sino-NK, June 28, 2013. 7 Kim Il-sung, Tasks of the Party Organizations in Ryanggang Province (Pyongyang: Foreign Languages Publishing House, 1958), 219. 8 Kim, Tasks of the Party Organizations in Ryanggang Province (1958), 231. 9 Ibid., 231. 10 Ibid., 232. 11 Ibid., 231. 12 Kim Il-sung, Tasks of the Party Organisations in Ryanggang Province (Pyongyang: Foreign Languages Publishing House, 1963), 276.13 Kim, Tasks of the Party Organisations in Ryanggang Province (1963), 277.14 Ibid., 291. 15 Ibid. 16 Kim Il-sung, Let us Make Better Use of Mountains and Rivers (Pyongyang: Foreign Languages Publishing House, 1964), 410. 17 Ibid., 416. 18 Kim Il-sung, Let us Make Ryanggang Province a Beautiful Paradise (Pyongyang: Foreign Languages Publishing House, 1974), 301.19 Ibid.,304. 20 “Model in Potato Farming,” Rodong Sinmun, January 10, 2013. 21 Ibid. 22 “Potato Planting Begins,” Rodong Sinmun, March 5, 2012. 23 “More Research Successes,” Rodong Sinmun, March 22, 2013. 24 “At Agro-Biological Institute,” Rodong Sinmun, June 13, 2013. 25 Heonik Kwon, “North Korea’s New Legacy Politics,” e-IR, May 16, 2013. 26 “New Potato Beverage,” Rodong Sinmun, January 25, 2013.

Rematerializing the Political Past: The Annual Schoolchildren’s March and North Korean Invented Traditions

Introduction

“Whan that Apriil with his shoures soote

The droghte of March hath perced to the roote…

So priketh hem nature in hir corages;

Thanne longen folk to goon on pilgrimages…” Geoffrey Chaucer – The Canterbury Tales – (General Prologue 2005,1387).

Geoffrey Chaucer’s fifteenth century narrative of pilgrims en-route to Thomas a Beckett’s shrine at Canterbury in England of course is a world away from contemporary North Korea. This chapter seeks really to make no connection between the two other than to reconfirm the cultural importance across time and space of the practice of pilgrimage and other such journeys. While pilgrimage has not faded from the world’s repertoire of cultural practice (Santiago di Compostella, Uman in the Ukraine and the annual Hajj to Mecca being particularly relevant contemporary examples), such practices are less familiar than in the past. But pilgrimage holds obvious advantages for the modern human; carving out time in busy human lives and creating shared and safe group experiences within a significant journey. But pilgrimage’s key feature as transmitted in secular, contemporary forms, has been its utility as vessel for the carrying, sustaining and socialisation of memory. New contemporary memories demand the creation of what Hobsbawm and Ranger (1983) declared invented traditions. These invented traditions support and underpin what Benedict Anderson named imagined communities (1983). Chaucer’s pilgrims, Hajji’s the Islamic world over and contemporary Irish visitors to the shrine of the Blessed Virgin Mary at Knock are very much part of imagined communities as Anderson would understand. These various communities pledge emotional fealty with their bodies and minds to community at its most loosely defined, to the Umma, to the fellowship of the faithful, to the ideologically sound. Together faith in the memory of something sacred and profound binds these communities together, constructing a framework of practice and praxis around those memories.

Invented Traditions and their Imagined Communities are not required to be either new products or of the deep past. This chapter does not suggest that Koreans as minjok (ethnic nation) are an Imagined Community. While disputes may rage as to the historical longevity or homogeneity of Koreans as an ethnic group, including any interruptions, ruptures or breaks in either longevity or homogeneity, this chapter does not suggest imagination is required on this point. Both Korean nations now present on the Korean peninsula have been subject to extraordinary historical and political forces in the last two centuries. Koreans have been forced to rethink what it means to be Korean in light of transformations in technology, capital, commerce, political and social organisation and notions of sovereignty. In more recent times Koreans have been required to imagine themselves anew once more. This time citizens on the Peninsula have had to define themselves as North Korean or South Korean, separated from family, brothers, sisters and minjok by what Paik Nak-chung described as The Division System (Paik 2011). While in 2018 it appears there may be unexpected gaps, cracks and fissures in the once monolithic separation, Koreans are still required to in some sense “other” each other by virtue of their location on the Peninsula. Much of that othering is undertaken through the function of a collection of new traditions, real, invented through which contemporary Korean sovereignty, statehood and communities are imagined.

This chapter looks to North Korean traditions which while vitally important to Pyongyang’s political structures, power and centralised institutional memory, are physically sited far from the capital, deeply connected and embedded within the landscape of its northern terrains. Paektusan is enmeshed in the political memory and practice of North Korea. Pyongyang refers to its political dynasty as the Paektusan Generals (Berthelier 2013) named after the memories of struggles in favour of Socialism and Korean nationalism in the mid-1930s by a select group of guerrilla fighters (under the control of a Kim Il Sung, if not the Kim Il Sung), against Japanese and colonial forces which is so vital to the framing of national history (Suh 1995). This group of political guerrillas would later emerge supreme over a number of other political factions in a young North Korea and would seal Kim Il Sung’s legacy. These memories and legacies are themselves invented traditions but this chapter does not privilege the grand narratives of North Korea’s leadership. Instead its focus is rather more prosaic traditions involving its ungarlanded citizenry. While it is virtually impossible to directly engage with North Korea’s public in situ, the invented and imagined traditions which surround them, which they are supposed to engage with and which literature and public media from Pyongyang can focus on with some intensity are certainly accessible. In recent years some of these new traditions have become incorporated into the institutional structures and training practices of North Korean bureaucracy and important moments in the timetable of the country’s school year. This chapter specifically focuses on the 250 Mile School Children’s March, an event first seen in 2015 and the study visits of North Korean bureaucrats and civil servants to Paektusan, visits which have increased with such frequency in the last five years as to become important traditions themselves. 2015 appeared potentially particularly impactful for North Korea’s developmental narrative given there were a number of important anniversaries that year which it would be vital to mark with new or renewed connections with the charismatic past.

Theoretical Frames

Aside from Hobsbawm and Ranger’s (1983) notion of invented traditions which is vital to the structure of this edited volume, its later intersection with Benedict Anderson’s articulation of imagined communities (1983), this chapter holds a number of other elements in mind within its theoretical frame. Both invented traditions and imagined communities must function within a wider ecosystem of politics, history and ideology. This chapter explores invented traditions within North Korea’s seemingly unique political framework. There are a huge variety of theories seeking to explain and explore the curiosities of North Korea’s politics. From concepts of North Korea as a gangster state, international security threat, quasi-fascist ethno-blood nationalist, place of institutional insanity, or bureaucracy focused on muddling through, even a rational actor, every stripe of ideological analysis has been directed at Pyongyang. This particular author holds to Heonik Kwon and Byung-ho Chung’s influential channelling of Max Weber and Clifford Geertz in their assertion that North Korea has all the hallmarks of a theatre state (2012), in which performativity has a vital political function and which might explain the longevity of its government and politics long after the collapse of the Soviet Bloc and similar ideological manifestations. Pyongyang’s theatric sensibilities are powered by a Weberian sense of political charisma deployed on a national scale, breaking temporal boundaries and embedding itself within the nation’s historical memory. As a human geography for the author of this chapter space, scale, boundaries and bounding are all vital elements within analysis. In North Korea space and place for political performance and practice is equally vital. Theatric politics necessarily requires a stage for the performance or re-performance of its charisma, that stage is the landscapes of the nation itself. This author therefore twins theories and concepts from anthropology (Benedict Anderson, Heonik Kwon and Byung-ho Chung) and history (Hobsbawm), with geographic theories on the construction of symbolic, political or social landscapes (Cosgrove 1984 and 2004; Castree 2001). Cosgrove determined that nations in the process of construction, literally build, generate or reconfigure new landscapes which best fit both national narrative, religious and political ideologies and cultural presumptions. Using the United States as an example Cosgrove suggests European settlers essentially rewrote the terrain of the future midwestern states such as Ohio, Indiana and Illinois (among many), from an unimproved, unorganized American landscape into a patchwork quilt of squares and rectangles reflecting European notions of property, gentility and cartography (or the science of map making). In small towns and cities in these emerging states, settler citizens and local bureaucracies would make certain to incorporate public parks and civilized amenities in new urban fabrics, attempting to bring the sensibilities of the old world into an at times hostile new world. Noel Castree’s conception of political landscapes (2001), building on Cosgrove’s work, suggested the direct embedding of political and economic ideologies into topographies and terrains. Utilising the critical approaches to nature of scholars such as Neil Smith, Michael Watts and David Harvey as well as that of Cosgrove, Castree engages with Marxist dialectics, and in particular Engel’s Dialectic of Nature, which was itself influential with those from whom North Korea would draw ideological inspiration (Winstanley-Chesters, 2015). Castree’s work would pave the way for contemporary geographic understandings of the overtly neo-liberal or economically conservative city with its predilections towards co-option and alienation of public space, and the privileging of spaces for consumption. Castree’s analysis connects with the writing of Eric Swyngedouw on scale as political practice within landscape (1997 and 2015), and the author’s own on the application of such ideas in North Korea (2015). Swyngedouw’s focus is the geography and hydrology of another particularly political territory, that of Franco’s Falangist Spain, examining the embedding of the ideologies of fascist modernity into a reconfigured national hydrology. Scale and scaling may be unfamiliar terms to readers in this context, given that originally they derive from the field of cartography and seek to describe the relationships between physical maps and the terrains which they aim to describe. Swyngedouw reconfigures the terminology of scale for the context of political, social and cultural geography, asserting that places represented or experienced by scaling are “the embodiment of social relations of empowerment and disempowerment and the arena through and in which they operate” (Swyngedouw, 1997: p. 167). Building from Henri Lefebvre’s conception that space and notions of spatiality themselves are products, social products, political products, this revisioning of scale is useful to articulate “…how scale making is not only a rhetorical practice; its consequences are inscribed in and are the outcome of, both everyday life and macro-level social structures…” (Marston, 2000, p. 221), as well as these reconfiguration of notions of charisma and scale. A particular population’s perception of the scale of their socially and politically constructed environment is not only shaped by their daily interactions with that environment – for example, commuting, working and so on, it is shaped by official state policies and governmental control of maps and cartography and other markers of space in order to influence people’s perceptions of their own environment. Government’s both democratic and autocratic utilise practices of scale and scaling to project narrative and frame both debate and social/political possibility across categories of time and space.

Notions of scale and scaling are equally applicable to North Korea, and these notions are determined by the daily practices of North Korean citizens (going to school and work, obtaining food, engaging in leisure activity) but also by the political elites of Pyongyang in their attempt to control the population. In North Korea these processes of scale and scaling are very much rhetorical practices as much as they are about impacting politically on social relations and utilising the charismatic energy described earlier through work of Kwon and Chung across time as well space. in addition therefore to the notions of the theatre state and scale and scaling there is one other vitally important theoretical concept that will help clarify the invented tradition of the Children’s March. hen it comes to scaling across time in North Korea and its invented traditions, these are best considered through the lens provided by Gilles Deleuze and Felix Guattari in Anti-Oedipus: Capitalism and Schizophrenia (1984). North Korean invented traditions and theatric energies are rescaled across time and space through the processes of what Deleuze and Guattari termed deterritorialization and reterritorialization. These are essentially used to articulate the processes involved in the fracturing, collapse or disintegration of situated social and cultural bonds between a physical terrain and the population or culture that inhabited it Much of their analysis revolves around the impact of capitalism on such cultural bonds and the pressures that alienated communities from their territories and traditional homes. While these processes transform and sometimes deeply impact on such cultures, they do not necessarily eradicate them and they can reform more powerfully or differently elsewhere. Deleuze and Guattari actually distinguish between absolute deterritorialization, in which the object of the process is completely destroyed or negated, and relative deterritorialization in which it reappears elsewhere or in a different moment. Good examples of this when it comes to imagined communities include two Eastern European visions of nationalism. Livonia and its language of Livonian was a pagan territory of Balto-Finnic people roughly occupying what is now northern Latvia and southern Estonia. Once a powerful coastal trading nation, who controlled the Daugava River, Livonia was devastated during the Livonian Crusade of 1198-1209, and never really recovered its position. Estonia was also the territory of another Balto-Finnic people long subsumed into more powerful nations such as Lithuania, Poland, Russia and Sweden. Estonia’s moment of independence before 1945 was also brief, nineteen years from 1920 -1939. Estonia and the notion of being an Estonian was deterritorialized for many centuries under historical rulers and from 1939 to 1991 by Nazi Germany and the Soviet Union (according to Estonian historiography), yet in 2019 there is a vibrant and energetic Estonian state, a member of the European Union, famous for its tech-savvy democracy. Its deterritorialization was only relative. Livonia on the other hand would never rise again from underneath the memory or curtain of another state. Today only 250 residents of Latvia and 30 residents of Estonia claim to be Livonian and the last native speaker of the Livonian language, Grizelda Kristina died in Canada in 2013. Livonia and its culture’s deterritioralization has certainly been absolute. An example rather closer to the focus of this article might be the attempt, as Korean nationalist historiography has it, of Imperial Japan and its colonial institutions between 1910 and 1945 to absolutely deterritorialize Korean culture and national identity by eradicating the Korean language and demanding a new Imperial subjectivity of its colonial subjects. Relative deterritorialization is of most interest to this chapter and to the consideration of North Korean politics and practices connected to it.

Readers will have gathered by now that this chapter is focused on what I claim to be a new invented tradition of North Korea, a series of annual marches which are connected to important moments in the nation’s history, in particular moments which were themselves journeys and crossings. Such journeys contain the charismatic political energy from which leadership and government of contemporary North Korea draw strength. This charisma is transmitted across time and into our and the North Korean present but not simply the processes of scale and scaling, I have previously talked about in this section, but also through these relative processes of de and re-territorialisation familiar to Deleuze and Guattari. The power of these journeys, crossings and charismatic moments is deterritorialized, abstracted and extracted from its original temporary and geographical context in the northern Korean peninsula of the 1930s and reterritorialized in our and North Korea’s present in the guise of the performative invented traditions described by this chapter. While Deleuze and Guattari did not originally include a temporal frame in their writing, doing so, so that such transformations also include de-temporalizations and re-temporalizations, allows for a more holistic consideration of the practices and implications of Pyongyang’s new invented traditions.

Since these traditions and the mythologies behind them occur close to North Korea’s border with the People’s Republic of China, and though the nation on the other side did not exist during those moments which generate so much charismatic energy for Pyongyang, the border and practices of bordering must have theoretical attention applied to them. Bordering and border crossing as practices and processes have themselves been subject to extensive theoretical framing (Singer and Massey, 1998 on Mexican border crossing and Grundy-Warr and Yin, 2002 on Myanmar border crossing as examples). North Korean border crossing in particular is considered to demonstrate the institutional and ideological failure of Pyongyang’s government. This is not the first time that border crossing has been problematic to institutional or national power on or near the north of the Korean peninsula. Korea or the Chosŏn dynasty’s (1392-1910) northern border has, nationalist narrative aside, always been semi-porous and in places undefined. Qing dynasty (1644-1912) and Chosŏn surveyors could not agree on the demarcation between the two in 1712 and 1885-1887 (Song 2016 and 2018). The diffuse nature of the boundary had not gone unnoticed and Korean settlers had problematically crossed the border and squatted on these debatable lands. Later this lack of definition would be used by Imperial Russia and Imperial Japan to problematise both Koreans in the border region and Korean sovereignty there at all (Song 2018). North Koreans crossing and re-crossing of the northern border are in contemporary times both problematised and idealised by Pyongyang’s opponents. North Koreans both engage in border crossing to become problematic migrants in China or South Korea (Chung 2008), or as a strategy for individual or group survival through practices of exchange and interaction with guerrilla or informal markets (Byman and Lind 2010). Both are in a sense problematic for Pyongyang itself, however analysis has suggested that informal border practices provide something of an escape valve for a system and its institutions which can no longer service much of their governmental responsibilities (Smith 2015). North Korea’s own historiography frames border crossers in the 1920s and 1930s as powerful actors and agents for national rehabilitation and re-creation. On the other hand, they were seen as extremely problematic to border and internal security by colonial and Japanese authorities (Haruki 1992). The reader will see how contemporary invented traditions from Pyongyang harness the energy of both of these conceptions of border crossing in the past.

Given the charismatic political construction manifest in North Korea, which utilises as one of the core elements of its authority and legitimacy a physical engagement in terrain and space within historical memory, so avowedly temporalized, namely the guerrilla spaces of Paektu, generating, producing and engineering through both performance, narrative and assertion a constructed landscape, would it not stand to reason, that such as social and politically constructed space could be iterated and transmitted by the processes of scale and scaling? North Korea’s political and cultural cartography in a sense is operationalized by its bureaucracy and regime at the national level. It is theorised and de or re-temporalized by this higher scale and it may be that in many circumstances it can be functionally useful in remaining at such an extensive and expansive scale. However, there are moments in which territorializing the charismatic spatial output of the wider, national production is a necessity in order to more realistically underpin or develop these narratives and their legitimatory content. At such moments we witness the transfer of charismatic content from one scale, the national and the institutional, to another, the locally spatial and the locally encountered. In these instances rescaling of the charismatic social and political constructions allows and supports the embedding and embodying of the narrative and productions, not just simply within the abstract body politic of North Korea, but in the physical bodies of residents and participants and in the spaces and topographies in which that charisma is performed and enacted. These spaces, rescalings, temporal enactments are at the core of this paper’s interest and to which it will now turn. To do so it will encounter three manifestations of such scalings and re-scalings, considering in particular those vectors, signals and processes by which they are operationalized.

The Deterritorialization of Pyongyang’s Sun

Readers who are already particularly interested in or focused upon North Korea will be well aware of the ideologies surrounding its dynastic leadership, whose role within the nation’s politics fully meets the definition of personality cult used in other instances of autocratic government. They might also be aware of some of the local distinctive peculiarities of North Korea’s personality cult. Kim Il Sung for instance, the first President of the Democratic People’s Republic of Korea (the official name for North Korea), is in fact the last President of the nation as he permanently holds that office, even though he died in 1994 (Yoon 2017). While forever having a dead President might seem unnecessarily odd or unusual, this extra-territorial, post-physical state of being in fact allows Kim Il Sung to serve more abstract and esoteric functions within North Korea’s political structure.

The Great Leader (one of Kim Il Sung’s many titles), serves as a vessel for memory and a carrier signal for the charismatic political authority generated as this chapter has already asserted, during the proto North Korean guerrilla period of the mid-1930s. In a further abstraction of Kim Il Sung’s physicality, one of the other titles ascribed to him is that of the “Sun” of the nation. As Pyongyang’s “Sun,” Kim Il Sung can permanently radiate beneficence, care and inspiration upon North Korea’s topography and territory, not subject to the impacts of time and aging (Suh 1995). His son Kim Jong Il and grandson Kim Jong Un, the current ruler of North Korea, as distinct and definite as they were political figures have also been abstracted a little by the impacts of this approach to both ideology and history. Kim Jong Il when younger and undergoing preparation or development for leadership in the 1970s was referred to North Korean publications as “the party center” rather than by name (Shinn 1982). Kim Jong Il is also referred to as the Dear Leader among other names and can be represented along with his father by the image of one of the national flowers of the nation; the Kimjongilia and the Kimilsungia (Oh 1990). Kim Jong Un himself is less abstract, but when describing his activities on a day to day basis, North Korean media still make sure, rather than grounding him in the present to place him within a continuum of memory that includes his father, grandfather and a variety of events and moments within North Korea’s memory (Rodong sinmun 2018).

In order to concretise these abstractions of political power and to better ground the complex narratives of history and memory required to underpin Pyongyang’s institutional power, constructed and invented traditions have been required. It is natural that a large number of these traditions revolve around the birthdays, moments of transition, triumph or other important days in the lives of its dynastic leadership (Gabroussenko 2010). Another chapter or paper could perhaps indeed focus on the invented traditions around the visits of one of the Kim family to factories, farms, hospitals and other institutions or pieces of infrastructure, which lead to these places being named after the day on which either Kim Il Sung or Kim Jong Il first visited them (Winstanley-Chesters 2015). This chapter however focuses on invented traditions which do not focus on infrastructure whether political, institutional or military in nature, and not directly on the leadership of North Korea as it is now constituted. Instead this chapter considers invented traditions which directly attempt to include members of its wider population and bureaucratic classes. Citizens of North Korea, no matter how politically engaged or institutionally connected, unlike the imagined traditions of their leaders live in concrete space and time. Citizens are therefore, regardless of how much effort central government spends on propaganda and political messaging, potentially disconnected in vital ways (from a North Korean institutional perspective) from the source and font of national ideological, philosophic or national inspiration. In order to bridge this disconnection Pyongyang has always sought to drive interest in the commemoration of important moments in the history of its leadership and charismatic political first family, or aspired to present an image of such interest where none might be actually present. A recent particular example of this tendency involved the 100th anniversary of the birth of Kim Il Sung’s first wife, Kim Jong Suk on December 24, 2017. Kim Jong Suk, born in 1917 is a figure somewhat distant to North Korea’s contemporary population, even with her blood and filial connection to the Great and Dear Leaders. While Kim Jong Suk already has a number of places named after her (such as Pyongyang’s Kim Jong Suk Textile Mill), December 2017 saw a large number of public events focused on both remembering her life, developing public interest in her narrative and embedding it within the minds of future generations. These events appeared to be a collaboration between central government, the Socialist Women’s Union of Korea and the Korean Children’s Union. Therefore, alongside the traditional wreathing laying ceremony at the Revolutionary Martyrs Cemetery (KCNA 2017a), the schoolchildren of Hoeryong watched and took part in a concert entitled ‘Eternal Sunray of Loyalty’ at Hoeryong’s Schoolchildren’s Palace (KCNA 2017b), KCNA asserted that interest in her and sites connected to her was “steadily increasing,” with some 300,000 visitors to Hoeryong in 2017 alone (KCNA 2017c). North Korea’s central bank printed gold and silver coinage with an image of her childhood home (KCNA 2017d), and the Ministry of Railways put a railway carriage and velocipede (a hand powered railway vehicle), on display that Kim Jong Suk has used in 1945 (KCNA 2017e). The crossings of Kim Il Sung this chapter considers in detail have also been matched with events of re-territorializing Kim Jong Suk’s own moments of crossing. Important moments of historical memory essentially serve as North Korean “Saints Days,” temporalizations and crystallizations of the supra-temporal and esoteric streams of narrative charisma. As well as a mythology such events also require a mythography onto which traditions and imagination can be implanted. While both the developing mythology of the North Korean political present has been considered by past academic work (Kwon 2013) and even the structural elements of the mythography onto which it is laid (Joinau 2014), what has not been addressed is the developing tendency for North Korea to provide opportunities and spaces for North Korea’s own citizens to encounter the narrative and charismatic energies transmitted by these “de- territiorializings” and “de-temporalizings” for themselves, to walk theatrically in the footsteps of the nationalist past. In doing so these citizens become actors and agents within the process of new invented traditions which seek to revivify the political energy of the past, bringing it physically into the present.

Far from Pyongyang and the current centers of political power and energy in North Korea, as well as the monolithic, commemorative architectures of the city, the Tumen and Amnok rivers on the nation’s northern boundary play a huge role in the way the rest of the world conceives of the nation. Gazing across the rivers from China, foreign eyes see a landscape of deprivation, barren nature and failures in governmentality and development (Shim 2013). However, these river boundaries have an enormous place in North Korea’s own self-perception. Long considered the boundary between Korean national territory and that of either China or Manchuria, the Tumen and the Amnok and their shores play a vital role in the histories of North Korea and Korean nationalism as transition spaces or zones of malleability (Winstanley-Chesters 2016). Travel through or interaction with these zones and spaces is in some Korean historical and mythological memories akin to crossings in sacred literatures of other rivers such as the Styx or the Jordan, crossings which transform and transfigure the crosser (Havrelock 2011). Another aspect of such zones and places are that they are seen within both mythologies, histories and hagiographies as places in which “special” or significant things are more likely or possible to happen than in other more conventional territory (Barthes 1972). New Testament Biblical texts even suggest that in such special places, a special temporal frame exists in which chronos, “chronological time” (χρόνος) is replaced by “kairos” (καιρός) or “special/significant” time (Smith 1969). Within North Korea’s historiography the landscape of the Tumen and the Amnok is subject to an interesting historical dualism, in which the spaces of the rivers are both zones in which things that are significantly bad can happen and where events which are particularly positive can occur. In North Korea’s historiography a number of key figures in the proto North Korean nationalist guerrilla movements, such as Kim Il Sung and his first wife Kim Jong Suk have important moments of crossing and re-crossing in their lives centered on these river zones (Winstanley-Chesters and Ten 2016). These important historical figures in North Korea’s national story are forced by the circumstances of colonial rule to flee across the rivers to the less distinctly Imperial space of Manchuria (later Manchukuo). They later return in a no less transformative a moment, crossing back over the rivers to begin their campaigns of guerrilla harassment of colonial forces, campaigns which of course later become foundational to North Korea’s notion of revolution and sense of national self (Suh 1995). In the process of crossing individuals such as Kim Il Sung and Kim Jong Suk not only support the transformation of the narrative of Korean or North Korean nationalism, but the transformation of their own selves. Connected via the transformative power of the de and re-materializing process of crossing and re-crossing into special or significant places and times, these important characters in North Korea’s history are transfigured from their child or precarious lives as colonial subjects, to powerful resistive, aggressive, political adults (Winstanley-Chesters and Ten 2016). Kim Jong Suk in particular was completely transfigured by her crossing, leaving a slight child of oppressed and destitute share croppers and returning across the Tumen river a politically aware, energetic expert in military tactics and excellent sniper (Winstanley-Chesters and Ten 2018).

Kim Il Sung’s own particular moment of river crossing, according to current North Korea historiography, occurred in January 1925 over the frozen waters of the Amnok River (Suh 1995). It was this crossing which in North Korean mythology begins the period of Guerrilla exile from which so much of his authority and charisma in Pyongyang’s conceptual mind derives. 2015 would be the ninetieth anniversary of this moment so perhaps it should not be surprising that the anniversary was marked. Rodong sinmun on January 23, 2015 reported: “A national meeting took place at the People’s Palace of Culture Wednesday to mark the 90th anniversary of the 250-mile journey for national liberation made by President Kim Il Sung” (Rodong sinmun 2015a). Neither was it surprising that the newspaper continued its report with a paragraph of assertions “On January 22, Juche [Chuch’e] 14 (1925) Kim Il Sung started the 250-mile journey for national liberation from his native village Mangyongdae to the Northeastern area of China. During the journey he made up the firm will to save the country and the nation deprived by Japanese imperialism. New history of modern Korea began to advance along the unchangeable orbit of independence, Songun and socialism” (Rodong sinmun 2015a).[i] As is common in North Korean media the text of the report attempts to include all three leaders produced by Pyongyang’s political dynasty. Kim Jong Il, the Dear Leader’s efforts to utilise this key source of nationalist power in 1975, through a commemorative march on its fiftieth anniversary is also addressed by the text. Finally space is also made for some of Kim Jong-un’s rather urgent and vociferous Paektusan focused themes found within 2015’s New Year’s Message: “Respected Marshal Kim Jong Un is wisely leading the work to ensure that the sacred tradition of the Korean revolution started and victoriously advanced by Kim Il Sung and Kim Jong Il is given steady continuity…calling on the school youth and children to hold them in high esteem as the eternal sun of Juche and carry forward the march to Mt. Paektu to the last.” (Rodong sinmun 2015a)

While repetition of past efforts and thoughts from North Korea’s leadership might not be surprising in such a medium, the mention of the march is the first moment in which the invented tradition considered by this chapter appears. Observers and analysts of North Korean cultural and historical practice are familiar with many of the traditions connected to its political mythology. Many engage the audience and citizenry in worshipful, passive veneration of North Korea’s political elite and their mythic past: standing in front of statues and monumental architectures, being shown sacred and important sites of memory, occasionally taking part in staged bouts of traditional dancing (Rodong sinmun 2018). So how would the school youth and children mentioned in the report from 2015 hold this “sacred tradition” in esteem, by passive participation at a meeting of the Workers Party of Korea? Through the singing of songs and poems dedicated to moments of nationalist history recounted by the text? By appearing slightly overawed or afraid next to Kim Jong Un during a moment of on-the spot guidance? In fact the answer would be none of these things, but something far more important, something that worked apart and aside from North Korea’s more conventional commemorative traditions. Instead of abstraction and narrative opacity, there would instead be a period of de and re-territorialization on the streets and paths of South Pyongan Province which itself would constitute a newly invented tradition. These schoolchildren would re-enact the crossing and journeys of Kim Il Sung in the 1930s, in the process using their own bodies as vessels and channels for the charismatic political energies rooted there for North Korean history. In short by this re-materialization of the political past, the children themselves become as Kim Il Sung and his small band of guerrillas.

There is a great deal missing in this first mention of this new tradition, much left out in the structure and conceptualisation, but this is not uncommon for North Korean political practices and praxis which often excludes content and coherence which might otherwise be expected. The process for the schoolchildren’s selection, the nature of the institutions from which they came, or their ages, the number of children involved, even the exact length of the journey (as it is unclear whether the schoolchildren walk the entire distance), elements which might support a really convincing re-enactment process elsewhere in the world and tie into political themes and agendas are never stated within the text of Rodong sinmun reporting of their enterprise. Yet the actual physicality and presence of their journey is clear and important to the narrative and the tradition. This physicality, common to pilgrimages elsewhere, perhaps even common to Chaucer’s pilgrims mentioned at the very beginning of this chapter, in which breaks, pauses and stops must be taken, presumably in this case to rest the children’s tired legs after having “crossed one steep pass after another,” is clear to the reader and a real element in the construction of this event (Rodong sinmun 2015b). These are presented as real children of North Korea in 2015, not simply cyphers for the pre-Liberation, nationalist past, revitalised by the ideological connection and charismatic energies of the history they re-enact.

Simply conceiving of this journey or pilgrimage as yet another theatrical moment in North Korea’s ceaseless flow of historiography and hagiography however would be to miss some of the important elements of the process and fail to draw out the greater and deeper levels of context and connection which underpin this new tradition. The theatric or performative potential of the event is clear. The children pass through, in North Korean tradition and practice a well prepared and well-trodden list of charismatic terrains, a list that is no doubt ideologically and narratologically entirely sound. Having left Mangyongdae, Kim Il Sung’s home village according to Rodong sinmun’s report, the children on the first march passed Kaechon (Kaech’ŏn, South P’yŏngan Province), Kujang and Hyangsan (both North P’yŏngan Province), Huichon (Hŭich’ŏn) and Kangyye (Chagang), “along the historic road covered by the President with the lofty aim to save the destiny of the country and nation in the dark days when Korea was under the Japanese imperialists’ colonial rule” (Rodong sinmun 2015b)

Following Deleuze and Guattari’s notion of deterritorialization, the spaces of relation and the practices of relation within the frame of the schoolchildren’s journey are equally as important as its starting point, route and destination, a fact held in common with much of the earlier narratives of North Korean journeying and crossing (Winstanley-Chesters 2015). Though within this newly invented tradition these children walk the route of the commemoration of what North Korea considers to be its period of national revolution and Liberation at this moment, temporally fixed in 2015, conceptually for those involved however it is supposed to be 1925. Whatever these North Korea children think in the quieter moments of their own particular everyday (perhaps watching South Korean TV dramas on smuggled in USB sticks, helping their parents engage in furtive transactions at semi-legal markets or coping with the mixed ennui of resignation, exasperation and desperation surely produced by daily interaction with Pyongyang’s institutions), the social and personal context of those “dark days” in the late 1920s is activated and actualised by their every footstep. When they stopped for breaks they would hear the “impressions of the reminiscences of anti-Japanese guerrillas” and beginning their march again the schoolchildren, following the political power of those reminiscences, would become, represent, even channel the affect, relation and aspirations of those same guerrillas (Rodong sinmun 2015b).

Following their departure from Pyongyang on January 22, 2015 these children, arrived at their (and both Kim Il Sung and Kim Jong Il’s) destination, Phophyong in Ryanggang Province around February 4 (Rodong sinmun 2015c). Phophyong, according to North Korean historiography, is the actual site of Kim Il Sung’s crossing of the Amnok River, the site where the young man would transition from subjugated Chosen (colonial period Korea) and the political frame of colonisation, to resistance in the wild edges of Manchuria and new commitments and practices aiming for personal liberation and political and ideological struggle. This was the place and moment of Kim Il Sung’s transformation and the foundational moment in this new invented tradition.

The North Korean historical narratives surrounding Kim Il Sung’s first wife, Kim Jong Suk also, as this chapter has suggested already have her leaving her hometown of Hoeryong (North Hamgyŏng Province), and crossing the Amnok River in the early 1930s (Winstanley-Chesters and Ten 2018). The crossing itself is conceived of in a similar way to Kim Il Sung’s as a moment of transformation, a harbinger of special times to come. It would not be surprising if other elements of this newly invented tradition of marching and re-materialization would be used to repurpose and reconnect with the charismatic energies of Kim Jong Suk’s crossing (Rodong sinmun 2014).

There have since 2015 been a wide variety of periods in which groups of children, workers, civil servants and others within the institutional and political frameworks of North Korean society and bureaucracy engage in such walks, marches and study tours (Rodong sinmun 2016, 2017 and 2018b). A number of these have marched and walked within some of the very same territory as the first march in 2015 (Rodong sinmun 2018c). The Schoolchildren’s March itself has been repeated again in 2016 and 2017 following a similar route, but with additions and subtractions on each occasion. Some have sought to connect other places and spaces of political memory and power into the routes of their walks and marches, still others have included museums and commemorative spaces themselves within the itinerary. The marching visit of the Korean Children’s Union to Mangyongdae and the Youth Movement Museum in June, 2018 serves as a good example of such walks (Rodong sinmun 2018d). It would be possible to frame these as more conventional acts of pilgrimage, if they were not deeply integrated into the ecosystems of North Korean politics. There have even been connections with the rich history of sacred spaces on and around Paektusan, in particular to the Secret Guerrilla Camp, the bivouacs, cooking spaces and campsites of the guerrilla campaign and even to the extraordinary slogan trees (Rodong sinmun 2018e). Paektusan’s summit has not been excluded from these practices and there have been a number of instances of study tours and marches of civil servants and bureaucrats visiting the peak of the mountain as part of their activities (Rodong sinmun 2018f). While surely visits and ideological pilgrimages to the sacred spaces of political memory in North Korea are not a new element to its conceptual repertoire of practice, there is something distinctly new about this category of invented tradition.

Conclusion

In ending this chapter let me reiterate what in fact is distinct in the North Korean context when it comes to this newly invented tradition. Kim Jong Un assumed power in North Korea in 2011, one of several family members that could have taken power. North Korea’s political system is rooted in and driven by political charisma, authority and legitimacy projected into the present by various processes as I have discussed at the beginning of this chapter. Kim Jong Un as a young, seemingly untested man, the son of an arguably unimpressive Leader, who had led his nation through difficult struggles profoundly lacked legitimacy at this moment and his authority was questionable. Much has been done to establish his legitimacy by North Korea’s institutions and government since the death of his father. The prime way this has been done is to connect Kim Jong Un to the historical, charismatic lineage, doing so through the transformation of his physical resemblance and connections to his grandfather, repetition of important images and motifs (Chollima and white stallions in particular, as seen very recently on top of Paektusan) as well as an awareness of the unpopularity of Kim Jong Il, and the relative popularity of Kim Il Sung. The School Children’s March (and perhaps other connected marches and organised political pilgrimages), which this article claims to be an invented tradition is part of these efforts towards connection to this deeper charismatic legacy, came just over a year after the violent purge of Jang Song Thaek, a reminder to both local North Koreans and the wider world of the factional struggles of Kim Il Sung and the brutality of the nation’s autocratic politics and government. At the same time of course the march is part of these ongoing attempts to legitimize the grandson of Kim Il Sung and bestow some of North Korea’s perceived historical charisma on him by further reiterating links to the legacy of the Paektusan Generals and Guerrilla dynasty.

The Schoolchildren’s March of 2015 has been repeated in 2016 and 2017, so in the end was not simply a one off re-enactment to connect to the particular energies generated by that year, or by the at the time impending 100th anniversary of Kim Il Sung’s first wife Kim Jong Suk in 2017 who also engaged in river crossings and much journeying around the same time (which have themselves also been remembered through acts of re-territorialization and remembering in recent years). These marches are also not commemorating one particular moment in the history of Kim Il Sung’s journeys and crossings, they do not follow a coherent or specific path of a single journey made by him. Instead as much as they re-territorialize collections of powerful moments, such as the crossings of the river, they are also assemblages of a number of different bits of historical narrative from the period within a geographical area generally considered to be charismatic within North Korea’s political history. Essentially the march is a repertoire of important moments of historical memory connected together in such a way as to amplify the charismatic energies present within each moment.

Beyond North Korea’s more conventional and historically familiar efforts to scale and rescale its political energies across its territory, the journeys reconfigured within the newly invented traditions which this chapter encounters and explores are in themselves also acts of rescaling. However more than the practices and processes of aligning the agenda of the periphery, North Korea’s more remote provinces such as Ryanggang and Chagang to the political aspirations of the center of power in Pyongyang, these traditions scale through and across time. Coupled with the processes of de and re-territorialization and de and re-temporalization the schoolchildren participants interact with the powerful political energies of North Korea’s mythological or historiographic past, the charisma on which the authority and legitimacy (perceived) on which Pyongyang’s Paektusan Generals sit, rescaling it into the present day and our own temporal plane. These marches, processes and journeys are themselves therefore scalar acts, as much as they are invented traditions. In the practice and process of these acts the participants are conceived of as not just re-enacting the journeys and travels of the past, cyphers and metaphorical vessels for them, but in some way they are transfigured into the physical realities of those who once, in North Korea’s historical imaginary trod the same paths and ground.

The Schoolchildren on the 250 Mile March in 2015 and other marches which sought to connect to the history and memory of Kim Jong Suk are thus powerful and as is the case with North Korea’s varied ideologies capable of many things, from serving as potentially transformative and transfigurative for those involved, to establishing a repertoire of newly invented traditional practices which can be and have been deployed elsewhere in North Korea. While they are extremely powerful and the practices of both scaling and de and re-territorialization at the heart of them can achieve much, there is one key thing that they and other invented or reimagined North Korean traditions cannot. In 2015 it was intriguing to consider their geographical place at the edge of North Korea’s sovereignty as in 1925 this area was also the edge of the Japanese colonial terrain. While later in the history of Japanese Imperialism Manchuria would be reconfigured as the puppet state of Manchukuo, in 1925 the other side of the Amnok river at this point was still nominally Chinese territory. The crossing itself of Kim Il Sung is vital to the narrative for North Korea. However, in 2015 the schoolchildren arrive at Phophyong, the site of this famous existential passage from one form of territory to another…yet they do not cross. Perhaps in those days of difficult and strained relations between Beijing and Pyongyang, prior to the events of 2018, such charismatic commemorations could not be enacted either side of the boundary of sovereignty. Perhaps given the importance for North Korea of ideological soundness, its schoolchildren never could in reality have crossed over into a different political space. Whatever the reason, the most important fact is that in this act of pilgrimage, this newly invented tradition focused on the re-materialization of powerful charismatic energies by those schoolchildren, at the moment and place of crossing, they cannot actually cross which leaves both the narrative and the invented tradition with a distinct disconnect, a functional void at its heart. Whatever aspirations North Korea may have at this point for this set of invented traditions, ultimately it cannot fully engage in their re-materialization. This newly invented tradition is for the moment at least trapped in North Korea’s political present.

Glossary

충격 여단 chungkyŏkyŏdan “shock brigades”

병사 건축업자pyŏngsa kŏnch’ukŏpja “soldier builders.”

Bibliography

Anderson, Benedict. 1983. Imagined Communities: Reflections on the Origins and Spread of Nationalism. Verso: London.

Barthes, Roland. 1972. Mythologies. J. Cape: London.

Berthelier, Benoit. 2013. “Symbolic Truth: Epic Legends and the Making of the Baekdusan Generals.” Sino-NK, May 17. https://sinonk.com/2013/05/17/symbolic-truth-epic-legends-and-the-making-of-the-baektusan-generals/.

Byman, Daniel and Lind, Jennifer. 2010. “Pyongyang’s Survival Strategy: Tools of Authoritarian Control in North Korea.” International Security 35(1): 44-74.

Castree, Noel. 2001. Social Nature. Blackwell Publishing: Malden, Mass.

Chaucer, Geoffrey. 2005. The Canterbury Tales. Penguin Classics: London.

Chung, Byung-ho. 2008. “Between Defector and Migrant: Identities and Strategies of North Koreans in South Korea.” Korean Studies 32: 1-27.

Cosgrove, Denis. 1984. Social Formation and Symbolic Landscape. The University of Wisconsin Press: Madison, WI.

Cosgrove, Denis. 2004. Landscape and Landschaft, Lecture Given the “Spatial Turn in History” Symposium German Historical Institute, February 19.

Deleuze, Gilles and Guattari, Felix. 1984. Anti-Oedipus: Capitalism and Schizophrenia. Athlone Press: London.

Deleuze, Gilles and Guattari, Felix. 1987. A Thousand Plateaus: Capitalism and Schizophrenia. University of Minnesota Press. Minneapolis.

Gabroussenko, Tatiana, 2010. Soldiers on the Cultural Front: Developments in the Early History of North Korean Literature and Literary Policy. University of Hawai‘i Press: Honolulu, HI.

Graves, Robert. 1955. The Greek Myths. Penguin: London.

Grundy-Warr, Carl and Wong Siew Yin, Elaine. 2002. “Geographies of Displacement: The Karenni and Shan Across the Myanmar-Thailand Border.” Singapore Journal of Tropical Geography 23(1): 93-122.

Haruki, Wada. 1992. Kin Nissei To Manshu Konichi Senso [Kim II Sung and the Manchurian Anti-Japanese War]. Heibonsha: Tokyo.

Havrelock, Richard, 2011. River Jordan: The Mythology of a Dividing Line. University of Chicago Press: Chicago, IL.

Hobsbawm, Eric and Ranger, Terence. 1983. The Invention of Tradition. Cambridge University Press: Cambridge.

Joinau, Benjamin. 2014. “The Arrow and the Sun”: A Topo-Myth Analysis of Pyongyang.” Sungkyun Journal of East Asian Studies 14 (1): 65-92.

KCNA. 2017a. “Wreaths Laid at Bust of Kim Jong Suk.” KCNA, December 24, 2017, http://www.kcna.co.jp/item/2017/201712/news22/2017124-14ee.html.[ii]

KCNA. 2017b. “Kim Jong Suk’s Birth Anniversary Marked in Hoeryong.” KCNA, December 24, http://www.kcna.co.jp/item/2017/201712/news22/2017122-12ee.html.

KCNA. 2017c. “Kim Jong Suk, Outstanding Woman Revolutionary.” KCNA, December 23, http://www.kcna.co.jp/item/2017/201712/news23/2017123-15ee.html.

KCNA. 2017d. “Coins to be Minted in DPRK to Mark Kim Jong Suk’s 100th Birthday.” KCNA, December 22, http://www.kcna.co.jp/item/2017/201712/news22/2017122-20ee.html.

KCNA. 2017e. “Mementoes Associated with Immortal Feats of Kim Jong Suk.” KCNA, December 22, www.kcna.co.jp/item/2017/201712/news22/2017122-11ee.html.

Kwon,Heonik and Chung, Byung-ho. 2012. North Korea: Beyond Charismatic Politics. Rowman and Littlefield: Lanham, MD.

Kwon, Heonik. 2013. “North Korea’s New Legacy Politics.” E-International Relations. https://www.e-ir.info/2013/05/16/north-koreas-new-legacy-politics/.

Oh, Kong Dan. 1990. “North Korea in 1989: Touched by Winds of Change?” Asian Survey 30 (1): 74-80.

Paik, Nak-chung. 2011. The Division System in Crisis. University of California Press: Berkeley, CA.

Rodong sinmun. 2014.[iii]“Leading Party Officials Start Study Tour of Revolutionary Battle Sites on Mt Paektu.” http://www.rodong.rep.kp/en/index.php?strPageID= SF01_02_0&newsID= 2014-07-31-0006&chAction=S, July 31, 2014.

Rodong sinmun. 2015a. “The 250 Mile Schoolchildren’s March,” Rodong sinmun, January 23. http://www.rodong.rep.kp/en/index.php?strPageID=SF01_02_01&newsID=2015-01-23-0004&chAction=S.

Rodong sinmun. 2015b. “The Schoolchildren’s March reaches Kanggye.” Rodong sinmun, February 3. http://www.rodong.rep.kp/en/index.php?strPageID=SF01_02_01&newsID=2015-02-03-0004&chAction=S.

Rodong sinmun. 2015c. “The Schoolchildren’s March reaches Phophyong.” Rodong sinmun, February 5. http://www.rodong.rep.kp/en/index.php?strPageID=SF01_02_01&newsID=2015-02-05-0007&chAction=S.

Rodong sinmun. 2018a. “Dancing Parties of Youth and Students Held.” Rodong sinmun, April 18. http://rodong.rep.kp/en/index.php?strPageID=SF01_02_01&newsID=2018-04-18-0012.

Rodong sinmun. 2018b. “Schoolchildren’s Study Tour Starts.” Rodong sinmun, March 17. http://rodong.rep.kp/en/index.php?strPageID=SF01_02_01&newsID=2018-03-17-0003.

Rodong sinmun. 2018c. “Schoolchildren Visit Mangyongdae.” Rodong sinmun, June 9. http://rodong.rep.kp/en/index.php?strPageID=SF01_02_01&newsID=2018-06-09-0004

Rodong sinmun. 2018d. “Youth and Students Make Study Tour of Revolutionary Battle Sites in Mt Paektu.” Rodong sinmun, June 26. http://rodong.rep.kp/en/index.php?strPageID=SF01_02_01&newsID=2018-06-26-0003

Rodong sinmun. 2018e. “Officials and Members of Agricultural Workers Union Tour Area of Mt Paektu.” Rodong sinmun, August 16. http://rodong.rep.kp/en/index.php?strPageID=SF01_02_01&newsID=2018-08-16-0020.

Rodong sinmun. 2018f. “Pak Pong Ju Inspects Samjiyon County and Tanchon Power Station under Construction.” Rodong sinmun, August 11. http://rodong.rep.kp/en/index.php?strPageID=SF01_02_01&newsID=2018-08-11-0009

Rodong sinmun. 2018g. “Pak Pong Ju Inspects Construction Sites in Samjiyon County.” Rodong sinmun, April 4. http://rodong.rep.kp/en/index.php?strPageID=SF01_02_01&newsID=2018-04-04-0008.

Rodong sinmun. 2018h. “Schoolchildren Visit Mangyondae.” Rodong sinmun, June 9. http://rodong.rep.kp/en/index.php?strPageID=SF01_02_01&newsID=2018-06-09-0004.

Shim, David. 2014. Visual Politics and North Korea. Routledge: London.

Shinn, Rin-Sup. 1982. “North Korea in 1981: First Year for De Facto Successor Kim Jong Il.” Asian Survey 22 (1): 99-106.

Smith, John. 1969. “Time, Times, and the ‘Right Time’; Chronos and Kairos.” The Monist 53(1): 1-13.

Smith, Hazel. 2015. North Korea: Markets and Military Rule. Cambridge University Press. Cambridge.

Song, Nianshen. 2016. “Imagined territory: Paektusan in late Chosŏn maps and writings.” Studies in the Histories of Gardens and Designed Landscapes 37(2): 157-173.

Song, Nianshen. 2018. Making Borders in Modern East Asia: The Tumen River Demarcation, 1881–1919. Cambridge University Press: Cambridge.

Stoddard, Robert and Morinis, Alan. 1997. Sacred places, sacred spaces: The geography of pilgrimages 34. Louisiana State University: Baton Rouge.

Suh, Dae-sook. 1995. Kim Il Sung: The North Korean Leader. Columbia University Press: New York, NY.

Swyngedouw, Eric. 1997. “Excluding the Other: the Production of Scale and Scaled Politics.” In Geographies of Economies edited by Lee, R and Wills, J., 167-176. Arnold: London.

Swyngedouw, Eric. 2015. Liquid Power. MIT Press: Cambridge, Mass.

Winstanley-Chesters, Robert. 2015. “‘Patriotism Begins with a Love of Courtyard’: Rescaling Charismatic Landscapes in North Korea.” Tiempo Devorado (Consumed Time) 2 (2): 116-138.

Winstanley-Chesters, Robert. 2016. “Charisma in a Watery Frame: North Korean Narrative Topographies and the Tumen River.” Asian Perspective 40 (3): 393-414.

Winstanley-Chesters, Robert and Ten, Victoria, 2016. “New Goddesses at Mt Paektu: Two Contemporary Korean Myths.” S/N Korean Humanities 2 (1): 151-179.

Winstanley-Chesters, Robert and Victoria Ten. 2018. New Goddesses at Mt. Paektu: Gender, Myth, Violence and Transformation in Korean Landscape (forthcoming). Lexington Press: Lanham, MD.

Yoon, Dae-Kyu. 2017. “The constitution of North Korea: Its changes and implications.” In Public Law in East Asia, 59-75. Routledge: London.

[ii] Korean Central News Agency, North Korea’s state news agency has several websites. In 2010 KCNA established a .kp address registered in North Korea, but this did not supersede the original www.kcna.co.jp address as this Japanese registered version has a searchable database going back some 18 years whereas the North Korea site only has the current years stories. Recently the www.kcna.co.jp site has been unavailable as it has been geo-blocked so that only browsers and computers accessing it from a Japanese internet connection can access it (NorthKoreaTech has a report on this at https://www.northkoreatech.org/2015/08/09/kcna-japan-site-isnt-down-its-geo-blocked/ . This was extremely frustrating to all that use it and enabled the commodification of the database through paywalled access sites such as kcnawatch. The fact that it should only be available from Japanese computers however is not a barrier to using it outside of Japan, so instead of paying to access these links, use a VPN like Tor, or install the Hola extension on Google Chrome and set it to spoof your internet connection so that it looks as if you are browsing from Japan. www.kcna.co.jp will then be free and accessible to you anywhere in the world. Download Hola from www.hola.org, download Tor from www.torproject.org

[iii] It must be acknowledged that due to North Korea’s habit of wiping the database of Rodong sinmun articles every year or two, the author cannot guarantee that articles from Rodong sinmun will still be available at the web addresses given. The author however keeps a copy of each Rodong sinmun article in a word document and would be happy to share any with interested readers. It is also worth acknowledging that these are the English language versions of the Rodong sinmun articles, Korean language versions of course exist and the author has copies of all of these as well. Again the author would be willing to share these with interested readers.

Fossil Fuel Futures for North Korea – Kim Jong Un’s 2019 New Year Address